Mexico’s chip plan stands up to the US

Unpacking the Mexican government’s ambitious semiconductor industrial policy.

Please enjoy this free article by The Mexico Political Economist—the only English-language outlet making sense of the noise surrounding Mexican politics, policy, and economics.

Do consider becoming a full paying subscriber to support independent journalism in an uncertain media landscape. Join the ranks of global government officials, journalists, diplomats, and top business and thought leaders the world round:

Europe didn’t wait for the dust to settle from the US-China trade war or the Covid-19 chip shortage. It saw the chaos and moved to return the semiconductor industry back to its shores. By 2023, the EU designed a plan, budgeted at €43 billion, to that effect.

Money in hand, member States distributed responsibilities according to their infrastructure and expertise. France and Germany got to become the centres for semiconductor factories (known as fabs). Holland was already strong in the materials needed for lithography, so the EU doubled down on that there. Spain got chip design and got to work on creating the Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

Over in Mexico, where no such initiative existed, Marco Antonio Ramírez Salinas, professor at the Centre for Computational Investigation at Mexico City’s National Polytechnic Institute (IPN) tinkered with challenges for his post-grads. Ramírez Salinas had got the idea from a colleague at MIT who taught by giving students concrete projects to learn from. One such project, started in 2010, really took wing.

It is called Lagarto (Alligator) and it is Mexico’s first domestically made processor. It was devised as a research project basically meant to follow in the steps of engineers past to land at a CPU from first principles. A few years in, they had not only done it, but had caught Europe’s eye.

The Barcelona Supercomputing Center asked, Ramírez Salinas said, if they could do a trade: Mexico City would transfer its technology to Barcelona, and Barcelona, in turn, would use its substantial funding to build an actual prototype chip—just one costs about $30,000 dollars—to see if the Mexican designs worked in practice.

The trade was a success. The Mexicans got the satisfaction of knowing their research was good. And, thanks to Lagarto, the Europeans were saved a decade’s work, Ramírez Salinas claims, which they put to work advancing the EU’s €43 billion-euro semiconductor masterplan.

“Wait, what?! How was that a fair trade?”, The Mexico Political Economist asked.

Ramírez Salinas smiled wryly and answered that, as an academic, it was most gratifying. From the rest of the conversation, though, it became clear why Mexico had been unable to make the most of its homegrown semiconductor research—and why it is confident a new government plan will finally allow its chip industry to take off.

Planning against US wishes

Last week, president Claudia Sheinbaum lined up the directors of the country’s most prestigious electronic engineering institutes to explain how Mexico would make semiconductors a pillar of Plan México, her administration’s ambitious industrial policy.

Contrary to the usual entrepreneurial and business feel of Plan México events, this was a particularly academic affair. Perhaps strange since Mexico’s challenges in this industry certainly seem very much economic in nature:

A third of Mexico’s trade deficit is made up of electronics imports. Of these, in 2023, over $24 billion dollars-worth were integrated circuits. Most were then added to products like electronics, household appliances, vehicles and then re-exported, leaving little added value in the country. Mexico uses a lot of chips but makes none, so choosing semiconductors for import substitution makes sense.

The world as a whole is keen to get a slice of the growing chip business. Over a trillion are manufactured every year and the industry is set to just keep growing—by about 20% yearly. Chips are also a matter of economic and national security. They are in virtually every electronic device and can be designed to slip private information to their makers through “back doors.”

Consequently everybody who is anybody has a chip strategy. Alongside the EU, the United States also has its own Chips Act, and in it, the US has big plans for Mexico. But, unlike the EU plan which is far more equitable among its member States in its distribution of added value along the chip supply chain, the US was generous enough to leave Mexico with the dregs.

There are three main stages in semiconductor making:

Design

Manufacturing

Assembly, Testing, and Packaging (ATP)

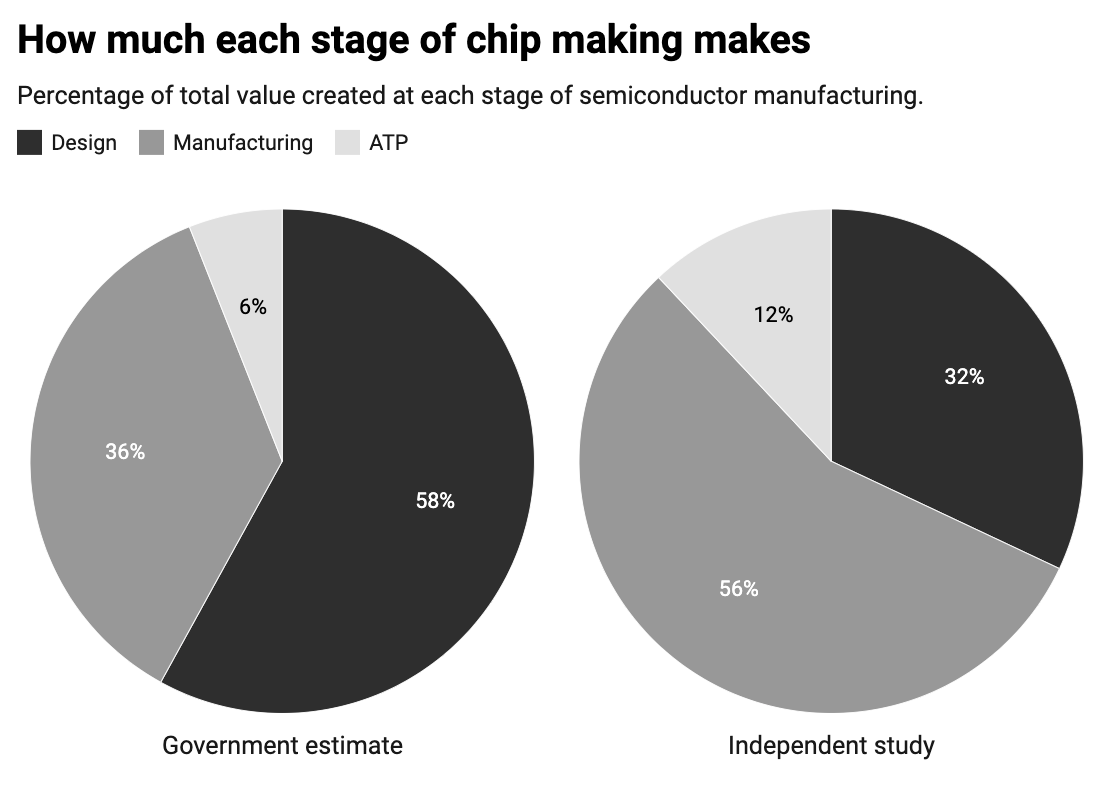

Not all steps are created equally. The Mexican government and an independent study meant as a roadmap for Mexico to enter the chip industry (worked on by The Mexico Political Economist’s founder) differ regarding how much value each step contributes to a semiconductor’s total.

On one front, however, there is no disagreement: ATP is by far the lowest value step. Unsurprisingly, this stage—the one most akin to the assembly industry Mexico is known for—is the one the US wanted its southern neighbour to do. Assembling, testing, and packaging US-designed and made semiconductors in Mexican chip maquiladoras.

Sheinbaum’s plan pushes back.

How Mexico’s semiconductor plan will work

Across the US-Mexico border, a decades-long, multi-billion-dollar chip project is underway. TSMC, the Taiwanese chip manufacturer making the most advanced semiconductors for all the world’s top laptops, smartphones, and AI, is setting up shop in Arizona, as part of the US strategy to bring this strategic industry home.

Mexico is nowhere near a project of that scale, but that doesn’t mean it cannot dream big.

Today, Mexico is home to just two companies in the semiconductor industry servicing Silicon Valley-level companies like Intel. India has 80. These are BigBang in Tijuana and Circuify in Guadalajara. Together they are hired to mechanically stress test chips by freezing, heaving, or overloading them. Even though the couple are competitors, they still wished there were more similar companies, since a proper ecosystem would attract the business of even more big firms to Mexico.

The annoying thing about the rise of Artificial Intelligence is that brand names like TSMC, Apple, Nvidia, or DeepSeek, have come to monopolise public awareness around chips. Certainly these companies design, make, or use most advanced microprocessors, but the world of semiconductors is far more vast.

For every sophisticated microprocessor, making up ‘the brain’ in any device, car, or appliance, there are manyfold more microcontrollers—call them the ‘nerves’ in a device’s nervous system. Each controls a single function in a complex device from toys, to washing machines, to medical devices.

This is the area Mexico wants to compete in, specifically in the very first step of the chip supply chain: design.

The country certainly has the market for it. As one of the largest exporters of semiconductor-heavy products—cars, electronics, medical devices—it has many companies to supply.

Added to this comparative advantage, design is also Mexico’s best bet in a cost/benefit analysis. Building a design facility can cost around $200,000 dollars. An ATP facility ranges from about $2-10 million (while, as noted above, providing the lowest value of the chip supply chain).

Mexico will thus be prioritising the creation of Kutsari, a semiconductor design centre.

Instead of relying on foreign money and know-how, the design centre will channel the expertise of researchers like Ramírez Salinas, train up Mexican engineers, and deploy them to supply the needs of manufacturers. This explains why, as opposed to other industrial policy events, Sheinbaum’s semiconductor presentation was so researcher-heavy.

The government likes to go on about how many engineers Mexico produces every year, but the quantity does not make up for the lack of specialists needed for this sector. The accelerated training in the design centre finally accounts for this.

Beyond the investments in creating a design centre, the Mexican government has also promised to streamline and strengthen semiconductor Intellectual Property (IP) laws. Mexican IP regulations are currently, by officials’ own admission, poorly designed and slow. The world average to process a patent like this is 3.5 years, in Mexico it’s 4.3.

Mexican inventors tend to patent their work abroad because their inventions are better protected and because it’s much faster. Mexico’s semiconductor plan will only work if Mexican engineers feel secure that their innovations are protected enough to be sent out and sold in the global market.

Where plans short circuit

Sheinbaum’s semiconductor plan is incredibly vague when it comes to how the chips will go from design to manufacturing to market.

There is mention of Mexico incursions into the manufacturing space by 2029 with private funding. The most likely way, said Bo Erik Gustav Hollsten Ruvalcaba, president and chief engineering officer of Cobeal, a US-Mexican company specialised in clean rooms, is for a foreign “company to come to Mexico, and in a few years you’ve got the plant and the tech.” The government would need to have clear a technology transfer policy to be able to build on this new fab lest the foreign company pack up shop and take its know-how and kit along with it.

Technology transfer is fine, Hollsten Ruvalcaba told The Mexico Economist, “but without starting with education, you’ve got nothing.” Mexico’s semiconductor academics need to link up with industry for Mexicans to learn the ropes, not as lever-pulling maquiladores, but as active adopters of this technology.

The Sheinbaum Plan is particularly inadequate when mentioning the chips’ final markets. Even the slide in the government’s presentation, showing the chip manufacturing pipeline, has “Market” pictured as a dim afterthought.

Speaking to experts and policymakers in the field, The Mexico Political Economist was told that the most likely route to connect designers with profitable markets was for the government to initially become Mexican chip’s main buyer. It could start by prioritising Mexican manufactures for the millions spent in acquiring USB drives, keyboards, and the like. The maker of one government-backed medical ventilator created during the pandemic, Ehecatl, has already identified one imported chip which is currently being substituted by IPN’s team.

Only after being founded and creating a successful portfolio, would private manufacturers in need of semiconductors have the incentive to start contracting Mexican chipmakers’ services. Again, growth would be gradual, with low-stakes microcontrollers for toys or electronic devices being the first chips to be bought by manufacturers as trust and expertise is built. The government could speed this progress by offering tax and other incentives to companies that actively source Mexican semiconductors.

Success, Ramírez Salinas said, needn’t be about money. It would depend on coordination of the existing but disparate parts of Mexico’s incipient chip industry, connecting those who have the knowledge, with the infrastructure, the capital, and the links to industry.

The Plan, for instance, could allow for the Barcelona Supercomputing Center to feed further research—born of the Lagarto chip prototype—back to Mexico’s design centre and into practical (and profitable) application.

If all goes well, Mexico would still be decades away from competing with the chip powerhouses like Taiwan, but it would be a good first step into properly entering one of the world’s most strategic industries on its own (and not the United States’) terms.

What an interesting text! Super necessary to know more about semiconductors, and I hope this is the first of many texts about it. I understand that it is not always easy to talk about these topics, but they are so important that we have to start knowing the language to speak it.