Mexico’s judicial election: A vote robbed of credibility

A convoluted vote count forced Mexico to fly blind on its historic judicial election. That should worry every democratically minded Mexican.

This is part two of a multi-part series on Mexico’s judicial election. Here’s part 1 if you missed it.

The Mexico Political Economist was an official electoral observer at yesterday’s extraordinary election in which Mexico elected all its judges and magistrates.

Stories already abound of empty polling stations and a perplexed electorate. Little information about thousands of candidates resulted in many depending on trusted political commentators and less trusted TikTokers to make their picks. Evidence of illegal party interference through the distribution of “cheat sheets” with government-picked candidates also abounded.

Hard-core political activists and enthusiasts put in the necessary days and hours to find the right candidate. Most Mexicans didn’t have the time for that and simply didn’t turn up.

The election failed to get people to the polls. Only 12% of Mexicans voted—the lowest number since Mexico became a full democracy in 2000. Many did so to spoil their ballots in protest (around 10%) with another 10% leaving their ballot blank. All of this could well put the effective vote below single digits.

This is a bitter win for the government, who seems to have got its desired candidates by default given the tiny turnout. It has also been an opportunity for nefarious actors to influence the process. The rushed and problematic electoral innovations to accommodate the convoluted nature of the vote might just have provided bad apples with the vulnerabilities they needed.

Heroic individuals vs systemic flaws

Volunteers drawn from everyday Mexican voters ran the election with the professionalism and enthusiasm that has come to define the country’s recent polls. The National Electoral Institute (INE) also did well. It whipped together an election as good as any could expect despite its restricted budget and even tighter prep time.

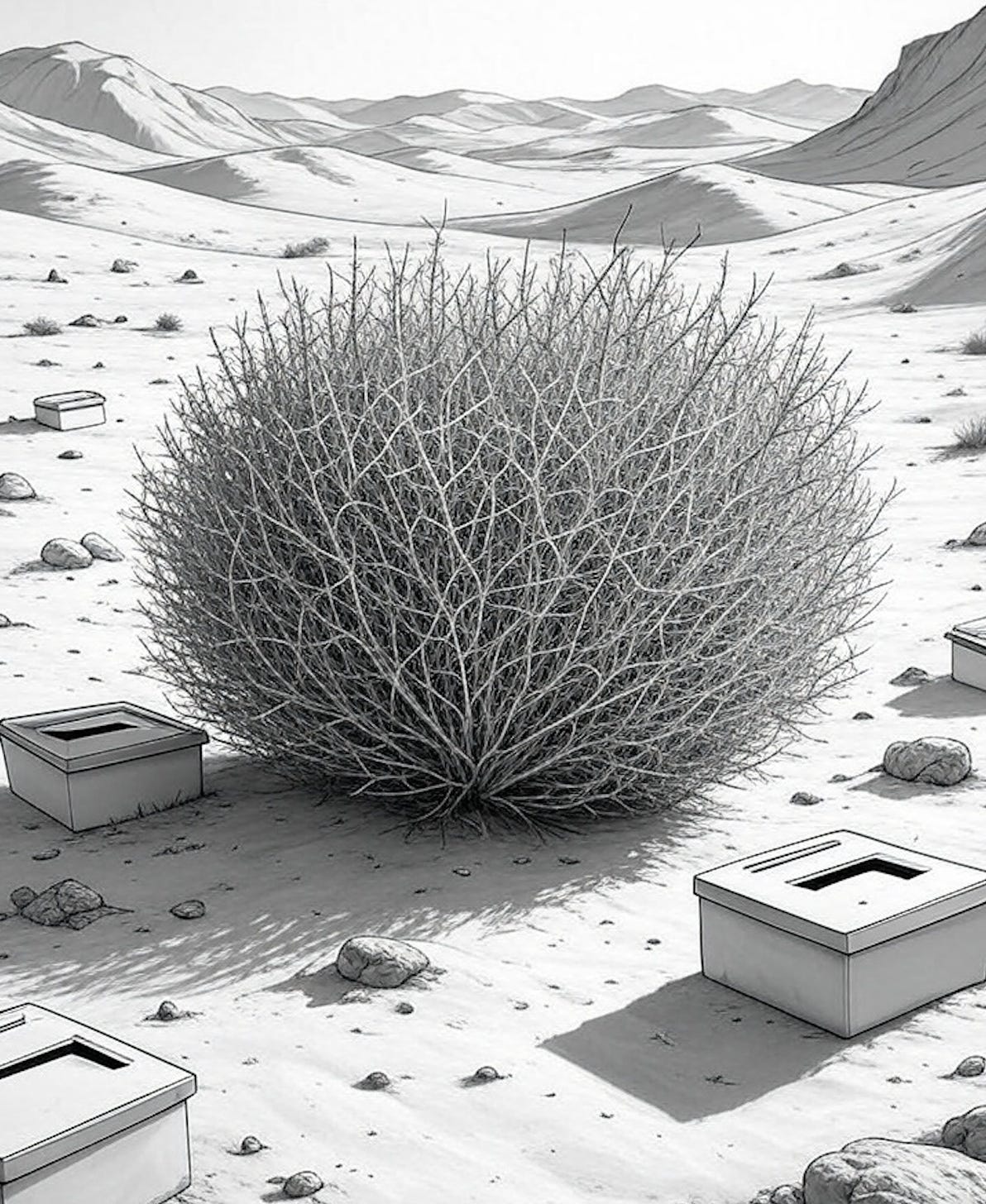

Ballot boxes, with their distinctive clear sides, were recycled from last year’s general election. Observers and citizens reported on a calm process. Everyone did their duty and made sure the election went smoothly enough.

Tellingly, there were waiting times and even some queues despite the small numbers of people. This was originally misinterpreted as an expression of greater turnout, it was in fact another side-effect of a downright unsolvable election.

Each voter took, on average, about 15 minutes to fill out the plethora of ballots they were given. They were charged with selecting all the way from the country’s top Supreme Court justices to local specialised magistrates with jurisdictional niches so specific that even lawyers friendly to the government and supportive of the election found it hard to explain who they were voting for and why.

Many voters were shocked to find they were getting three or four more ballots than they expected. It turned out that they hadn’t counted on the separately organised local judicial elections. Worryingly, it is this state-level justice with which most Mexicans will actually have to deal with of they ever get in legal trouble.

Still, up until that point, the system held. Polling station officials patiently guided voters without telling them who to vote for. Later, ballots were meticulously separated into their respective colour-coded categories (purple for Supreme Court justices, mint green for the Judicial Disciplinary Tribunal, and so on). Unused ballots—the vast majority—were separated and sealed for disposal.

It was at this point that things started to become problematic. In every other one of Mexico’s citizen-run elections, those same volunteers would count the votes there and then at the polling station, under the watchful eye of party, independent, and international observers.

Not so this time. The count will be so vast and long, with so many positions to account for, that counting is still happening in each jurisdiction’s electoral HQ.

As one of those observers, The Mexico Political Economist requested the INE official shuttling the packets of ballots to join them in the ride over to one of such HQ in the Mexico City borough of Iztapalapa.

“You’re not allowed to,” came the answer not only from the local official but also from a senior INE supervisor, Alejandrina Granados Roldán.

A massive electoral blindspot came view. For the next hours, the ballots holding the future of Mexico’s judicial branch travelled as of yet uncounted and unobserved by neither local nor international observers.

The people who were allowed in the ballot shuttles made this even more problematic. At least in Iztapalapa, INE—which has been deprived of its usual budget for this election—hired vehicles and drivers from a notoriously partisan taxi union. The Coalition of Taxi Drivers of the State of Mexico harken from and are contracted by the aforementioned state, one run by Morena—the ruling party. The shuttling was not a novelty in itself, what became a worrying innovation was that this time, ballots disappeared for a good while before anyone had had a chance to count them.

There are no indications that any foul play went on in the transport of the ballots. Then again, observers—whose task is exclusively to follow the ballots every step of the way to ensure a clean vote—couldn’t possibly know if anything unseemly did take place in those hired shuttles.

It is oversights like this which bring an already extremely controversial election into further question.

INE officials that spoke to The Mexico Political Economist emphasised that Mexico’s electoral system is strong and designed to identify and prevent any such malfeasance. But, even on Election Day, reports of pre-filled ballots in the northern state of Sinaloa and stolen ballot boxes in the southern state of Chiapas began to crop up.

INE no doubt dealt appropriately with these specific instances, but the question is whether the judicial election’s specially-crafted vote counting system opens up other, hitherto unknown avenues for interference.

The government and the ruling party will surely brush such worries aside, as they have throughout this whole process. Long gone are the days, when it was in opposition, when Morena would have taken to the streets in protest for far less.

The blame game

Mistakes and oversights in this rushed election will be compounded by the dismal turnout.

Some Morena supporters are already trying to pin the election’s perceived failure on INE—with a few half jokingly suggesting maybe it should be the next government institution to be reformed by the ruling coalition.

INE did far better than could be expected with the resources and time it was given. That cannot be said of the opposition, who decided to sit the election out, freely handing power to a government they have consistently accused of trying to seize it.

The government will celebrate, yet its electoral machine seems to have failed. Its preferred candidates will dominate the courts, but internally there are worries that they won chiefly because the opposition stayed home. There are rumours of a cabinet reshuffle in the Sheinbaum administration.

Meanwhile, most Mexicans have been left scratching their heads. What have they actually voted for? Searches for judicial terms on the ballot exploded just hours before polling closed, falling immediately as the clock struck 6pm closing the day’s electoral proceedings.

At least for the next few years, justice in Mexico will continue to be out of average Mexicans’ hands. The judges have been chosen.